|

In a community where the minority language is French, many activities are conducted mostly in English, the dominant language. For example, television, tablets, social media, reading, recess and extracurricular activities. Furthermore, we are seeing more and more English dominant (ED) children enroll in French-language schools. These children are learning French (the minority language) in a French-language school all the while living in an English community. On the flip side, the French dominant (FD) children are also learning French in a minority context but they are increasingly exposed to English through their French second language (L2) learning peers. This significantly decreases their opportunities to hear and to use French and makes it more difficult for them to acquire and maintain the minority language. Usually, a typically developing francophone child who starts school will use his or her previous knowledge to expand his or her vocabulary in the language of instruction. However, a typically developing Anglophone child will have little to no prior knowledge available to help broaden his or her vocabulary in the language of instruction (French). Learning new words can be done in two ways. It can be done explicitly, where the child understands the word with an explanation using familiar terms, for example “This is a buff. It is a type of clothing that we can wear in the winter to keep our neck warm.”. The child might use some of the familiar words such as clothing, winter and keep our neck warm to help him or her understand the meaning of the new word buff. It can also be done implicitly, where the child discovers the meaning of the new word from the familiar terms that surround it. For example, “The cold wind didn’t prevent her from playing outside because she was wearing her warm buff”. In this example, the child must use the words and context of the sentence to deduct the meaning of the new word. A child who doesn’t have a lot of vocabulary knowledge will find it difficult to use the latter method to learn new words. Therefore, for the most part, English-speaking children who attend a French-language school will need to learn new words explicitly! We wanted to know if children living in linguistic minority communities were sufficiently exposed to the French language in order to acquire the French vocabulary. We compared the vocabulary test scores of 25 French dominant children and 35 English dominant children aged 5 to 6 to those of the monolingual norms. The results showed that when ED children were assessed in their dominant language (English), their performance was similar to the English monolingual norms on receptive and expressive vocabulary tests. When FD children were assessed in their dominant language (French), they were unable to achieve the monolingual standard on receptive and expressive vocabulary tests. The results also showed that in all cases, the children performed better in their dominant language than in their L2, which is to be expected. However, it seems that when the dominant language of the child is a minority language, the acquisition of vocabulary becomes more difficult in this language because of the linguistic minority context. This can be explained by several factors, but the one that stands out the most is language exposure. We also looked at the languages used at home for each of the children in our study; one francophone parent and one anglophone parent, two francophone parents, two anglophone parents, etc. What emerged was that regardless of the languages spoken by the parents, French dominant children were always less successful on the French vocabulary test than their francophone monolingual peers. All children were less successful in their L2, but these results were even more pronounced among learners of French as an L2. This can be explained by the fact that not all English speakers speak French, but all (or almost all) French speakers speak English. In fact, in another study conducted on Franco-Ontarian participants, the performance of French dominant participants on tests assessing the language proficiency of five-to six-year-olds was weak compared to their Quebec peers. The performance of monolingual Franco-Ontarian and FD children seems to be strongly affected by the linguistic context in Ontario. Is there no hope for the promotion of French language in a linguistic minority context? The questions that remain after this study are: "With more years of schooling in French, does the vocabulary of bilingual FD children resemble that of monolinguals’? Will the vocabulary gap between the ED and FD children diminish?" and "How many years of exposure and instruction in French are needed to ensure that ED children acquire a vocabulary comparable to that of Francophone or FD children residing in the same region?" Gervais & Mayer-Crittenden, 2018 For more information on how to widen your child's vocabulary, click on the PDF below.

*** This post can also be found on Speech-Language & Audiology Canada's Blog: Communiqué by clicking here.

Have you ever heard an adult say “I used to speak French as a child but now I feel much more comfortable speaking English?”. This is a very common phenomenon called language dominance shift. It is seen most often in regions where children are exposed to the English community language more than their native minority language. For some, it’s a lifelong struggle to maintain proficiency in a minority language where one has to constantly seek out opportunities to practice that language. If you don’t use it, you lose it! What about those who have a developmental language disorder (DLD)? Can they maintain proficiency in their minority language? What is DLD? Researchers agree that DLD is a neurodevelopmental disorder with genetic components. DLD interferes with a child’s brain development which, in turn, causes difficulties with language learning. Children who have DLD have difficulty understanding language, learning language and talking. They may have a hard time putting sentences together, using the proper grammatical verb endings or even coming up with a word they want to use. Children with DLD often use simpler language than their same aged peers. Some may even omit certain parts of words and at a young age, might sound like they are mumbling. The latter usually improves with age, but many other difficulties persist. Children with DLD might also have difficulties with their receptive language. However, this is much less obvious. Some might seem like they are not paying attention or like they are misbehaving or even lazy. When in reality, they might only be picking up odd words here and there, but not grasping the full message, making complex sentences a real challenge This can be due to a difficulty figuring out the meaning of words. Most longer words are not frequently used so those might be difficult to understand. The same goes for words that are difficult to imagine. If I say “apple”, a picture of an apple usually pops up in your head, but if I say “dimension”, that word is difficult to represent by an image and is often more difficult to grasp. To Speech-Language-Pathologists (SLPs), these difficulties may seem somewhat obvious. To an elementary teacher, a daycare provider, a tutor, or even a parent, these difficulties sometimes go unnoticed. Disorders like dyslexia, ADHD or autism typically have much more obvious symptoms, which is why so many more people know about those disorders. DLD is a hidden disorder, making it that much more difficult to identify. It’s important to identify kids who have DLD at an early age. However, this is often difficult, even for a trained SLP when children are learning more than one language. Bilingual children who are at risk of DLD might appear to be having difficulty learning the second language, when in reality, their difficulties show up in all languages. We know that solid first language development can have a facilitative effect on second language acquisition. In fact, difficulty learning the first language means that these children will end up with inadequate skills in both languages. It has been shown that insufficient abilities in the first language adversely affects second-language development. So how can we prevent this? The key is often language exposure and early identification. For both typically developing kids and those who have DLD, most will have a dominant language and a non-dominant language. The dominant language is typically the language for which they have received the greatest amount of exposure. However, the dominant language can shift over time such that children who learn a majority language (i.e. English) as a second language often end up becoming dominant in that language. The maintenance and continued development of skills in a minority first language depends on how much exposure they get in this language. Some experts say that children need to be exposed to a language 40% of their waking hours in order to become proficient in that language. In these instances, studies consistently show that from early to middle childhood there is a shift to greater proficiency in the majority language. This is due to the rapid acquisition of the community language together with the slowing, stabilization or loss of the minority language, a consequence of different social experiences, opportunities and demands for the two languages. Note that this is not the case, however, for children who learn the majority community language at home (i.e. English) and attend French-immersion programs for example. Studies have also shown that young children who have a minority language as their first language and who have DLD are even more vulnerable than typically developing bilingual children to lose their first language or show early plateaus if this language is not supported. As a parent to a bilingual child with DLD, I battle every day with these notions. My daughter learned English at the age of about 4, making her a sequential bilingual. French is her first language, but we live in a predominantly English community. Even at her French school, children often converse in English in the hallways or in the school yard. She spends roughly 42% of her waking hours in English and 58% of her time in French*. I was stunned by these numbers because I always felt as though she was exposed to a lot more French than that. However, when I actually broke down her week, it made sense. My husband and I speak English to each other and she swims competitively for the local synchronized swimming team where all of the activities take place in English. Several kids in the neighborhood with whom she plays are Anglophone and she only watches TV (Netflix) or YouTube Kids in English. Minutes become hours and hours add up quickly! I have always spoken to her in French and my husband learned the French language with the kids so he speaks to her mostly in French as well. However, I noticed during the summer break, and even more so over the recent Christmas holiday break that she seemed to naturally default to speaking English to myself and to her siblings. Whereas my other two kids continued to use French spontaneously. I calculated the hours of exposure for that week between Christmas and New Year’s Eve and the percentages changed drastically. For one, there were fewer hours of language exposure, which is to be expected because children often take on activities that require very little talking, ex. drawing. For two, she was mostly exposed to the English language due to family visits with my husband’s side of the family as well as time with friends and activities such as downhill skiing and public swimming. Overall, my daughter was exposed to the English language 85% of the time and to the French language,15% of the time. This change in language exposure seemed to turn off or dim down her French language switch and I had to constantly remind her to speak French to me and to her brother and sister. Once school resumed, this was no longer the case! Her French switch was turned back on, so to speak. I find the analogy of a dimming light bulb fitting. Bilingualism is a continuum. Our brains can have two or more dimming light bulbs at any given time and languages are activated according to our environment. We can dim one language and have the other one on high ampere (amp) or we can have both equally activated at the same time. It might be that children with DLD have weaker amps but they are still able to learn and maintain two languages. One language might just get dimmed or turned off must faster than it would for typically developing children. I found this fascinating and did a bit of research to see if this had been studied. From what I could find, nothing has been done on this topic. Is this an indication that her language dominance may eventually shift to the English community language? Are the cognitive demands too high for her to consciously use the French language when submerged in an English environment? Is this the case for most children with DLD? Food for thought. I hope to find out! *In order to help parents make this calculation, I have created a form that can be used for this purpose: http://www.botte-boot.com/uploads/4/8/2/6/48260095/exposure_mapping_english_updated.pdf Chantal Mayer-Crittenden, 2017 It’s mid-summer and I have been enjoying my down time with our three kids. One week on, a couple of weeks off, another week on… It’s been good. As I sit here, a bystander listening to my kids play by the water, it baffles my mind to hear how they use languages. To them, languages are a means to get their point across or to get their needs met. They speak English to our dog, English to their cottage friends, to my husband’s side of the family, to their campmates at their bilingual summer camp as well as with most friends from our neighbourhood. They usually speak French to me and to their dad as well as to my parents, except when they are surrounded by their English-speaking friends. In those instances, they will sometimes turn to me and speak English so I try to make a point of asking them to switch to French but I am sometimes reluctant to do so, for fear of sounding punitive. “Parlez français” [speak French!], is what I hear myself saying over and over again.

Here’s a sample of what I am hearing while I write this post. I am outside in our gazebo and they are swimming in the lake: Matt: French: Je vais retourner avec mon bateau. [I’m going back with my boat] Sarah: French: Je vais sauter. [I will jump] Matt: English: Let’s go, I’m going tubing. Julianne: English: Sarah let's go. Sarah: English: Matt I said I was jumping. French: Je sais, je veux sauter [I know, I want to jump] Matt: English: Sarah hurry up. French: Julianne assieds-toi en avant [Julianne sit in the front] They switch from one language to another for no reason other than because they can! What gets me going is when the words within their sentences are so mixed up between languages that I actually have to stop and think about what they are saying. I will often make light of that and give them an inquisitive look. I explain to them that it’s okay to mix up the languages, but that whenever possible, they need to take a few seconds to think about the words they are looking for and use one language in one sentence. Here’s an example of such code-mixing I just heard in the last 5 minutes: Julianne: Je wish que je pourrais diver off le dock” [I wish I could dive (with French verb ending) off the dock] What I normally do is repeat what they say by giving them the right words. In this case, I could have said: “Ah oui? Tu souhaites de plonger en bas du quai ? Vas-y!” [Oh ya? You wish you could dive off the dock? Go for it!”]. Sometimes they repeat what I have just said and other times they carry on with what they were doing. The interesting thing is this: very seldom do they use French words when they speak English. It’s usually the other way around. They use English words when I know for a fact that they have the French words in their vocabulary. Other times, I catch my three French-native children speak English to each other, like the example above, which is a great thing don’t get me wrong but I worry at times that they don’t get enough French exposure. In this age of iPods, iPads, AppleTV, Netflix and iTunes, they are inundated with English media to the point that French TV and French music are now the less preferred choices. I try to purchase French TV series and French music when I can, but it’s as though their default for media is now English. We try to set some time aside a few days a week to read in French. Luckily, French is still their default language when it comes to reading. Mainly because in Ontario, they only formally learn to read in English in grade 4, at the age of 10. Why do I care so much? I guess it’s because French is the minority language here. Kids and teenagers usually end up speaking English to each other, even if they all have French as their first language. Most Francophone adults, who are actually bilingual (English as the second language), end up working in English the minute they get their first job. Work in French is usually limited to positions within the French school boards or specific government-funded programs that promote the French language. So English ends up being heard and used all over the place. Since French is my heritage language, I really want to pass down that heritage, culture and language to my kids. My husband, who learned French as the kids spoke their first words, is also very intrigued by our kids’ use of their two languages. He will often ask them to speak French to each other or better yet, point out to them when they are mixing up their languages! He understands the value of encouraging the use of the minority language and for that I am grateful. It’s a real battle. I’m extremely conscious of the importance of promoting the French (or minority) language to our young ones, but I struggle with the means to meet that end! Here are a few tips and tricks that have worked for us:

For more tips, check out these handouts that I have created:

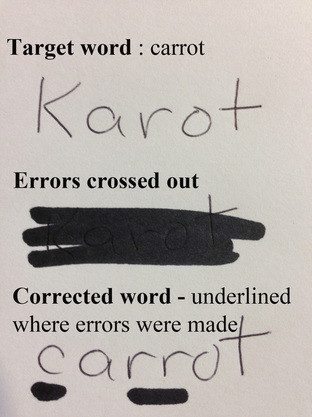

I've written a lot about my daughter in past posts but I failed to mention that my son has a mild learning disorder with a mild dysfunction in reading and writing skills. He was diagnosed by a psychologist when he was in grade 3 at the age of 8. He is now in grade 5 and has come such a long way, thanks to the help of his teachers, support staff and the advice from my dear colleague Dr. Michèle Minor-Corriveau. Written language isn't my area of expertise and to be honest, we didn't receive a lot of training in this domain when I was completing my master's degree in Speech and language pathology. I am so grateful to have an expert in the field who is willing to work with my son and provide consultations to the school staff. I asked her to write a post for my blog so that she could share with other parents, teachers, caregivers and speech and language pathologists exactly what is a written language impairment and how we can go about helping those who struggle with writing. You can read more about Dr. Minor-Corriveau at the end of this post. Here is her post... If we were dropped off on a deserted island void of alphabet, written words, signs or messages, we would never learn to write, nor would have the need to. Social beings that we are, we would, however inherently develop an oral language common to the natives found on this deserted island in order to communicate needs, wants and desires. Written langage, however, is a code that must be taught explicitly : it is not acquired simply by interacting with other social beings. So how do we decide which skill to teach first ? The answer to this question is not a simple one, nor is it clear cut. The answer to this question far exceeds the limits of this post, but it should be well understood that learning written language is not linear. One does not master the art of spelling and writing accurately without explicit instruction, or by summing up different skills to make a whole. In this case, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and given the diversity of children’s abilities grouped together almost randomly in any classroom, a one size fits all approach is rarely effective. Who decided that age was the most common characteristic that children share? That is, however, the most common factor considered when grouping them together in an effort to teach them new skills. That too is a discussion for another post. Suffice it to say that, in French, there is very little to guide teachers in the manner in which to teach spelling abilities, but there is a recommended hierarchy that, when followed across a continuum, would help children efficiently master the basics. And although mastery of one competency can lead to mastery in another, this is not a guarantee of success and some insight is needed to choose which skill should be targeted next. I suggest reading up on Pothier to gain a better understanding of this concept. Of the utmost importance when teaching children to spell and write, is knowing what type of spelling errors they are making. So what are the different types of spelling errors? Let’s be clear: children, at one time or another, exhibit every type of error. It is part of a natural learning curve. Even as adults who consider themselves to have mastered the written code, these errors often creep into our lives. Knowing how to identify the type of error you are trying to avoid or remediate can help to troubleshoot and provide strategies that will allow your child to increase written language proficiency. Common error types include, but are not limited to: syntactic, lexical and phonetic/phonological errors. When a phonetic/phonological error is sounded out, the word is not phonetically identical to the target word. For example, when the word ‘carrot’ is spelled ‘garrot’, that would be a phonetic error. If the word ‘carrot’ was spelled ‘carott’, then that would be classified as a lexical error. Syntactic errors can only be analyzed within the context of a sentence, since they can only occur when agreement between words or clauses is inaccurate. So what can be done to help save our children from disastrous spelling? Here are a few ideas that might help to increase the likelihood of error-free spelling. Know your child’s error type : Knowing the type of error that has been made can help provide a strategy to wipe out the error next time. Phonetic/phonological errors CAN be eliminated when you ask your child to sound out the word, but this strategy isn’t sufficient in and of itself since children will often sound out the word they originally wanted to write. A high level of insight is required to use this strategy as a means of correcting mistakes. This type of error should be one of the first types to disappear, once children’s phonological awareness skills are mastered. Lexical errors can be corrected using a dictionnary or a word prediction software such as WordQ or Medialexie. For those who are still spelling phonetically, there is an answer : using a phonetic dictionnary such as Lexibook or Franklin. These technological devices and software serve more functions than those that are listed here. Syntactic errors can only be eliminated by learning the ropes. And by ropes, I mean syntactic competencies. A word of caution: students will not master all of these skills at once, so a high tolerance for errors related to the skills that have not been taught is required to maximise student performance and interest in writing. Invest in a Sharpie : it’s an easy, fast and cost-effective way to block out mistakes. If a child makes a mistake, use the sharpie to block it out, so that he/she never sees it again. Write the word correctly above or below the blocked out word, and underline the area that should be focussed on. For example, if a child writes ‘carott’, you block it out and write ‘carrot’. That way the memory will focus on the underlined parts, and the odds of retaining the correct spelling has increased. Think of it this way : if a child must look at his error, in order to decipher and write the word correctly, he/she is exposed to the error more than the correct spelling, which increases the likelihood of making the same mistake over and over again (see picture at end of post). So here’s to teachers and parents everywhere! Let’s band together and help our children use all of the resources that are readily available: dictionaries (whether they’re paper-bound or virtual) and encourage them to embrace the difficulties of written language as part of the process. We need to change children’s perspectives: everyone makes spelling mistakes. It is only when we are aware of them and the tools that are available to help minimize them, that the battle can be conquered. Corrections and constructive feedback are not equivalent to criticism. Each child should be encouraged to master skills at his or her pace, and the only competition should be with oneself. Stay tuned for upcoming posts from Dr. Minor-Corriveau in which you will read about: · Can a student who is still learning a skill actually make a mistake? · Is access to a spellcheck function more of a help or a hindrance where spelling ability is concerned? · What are the challenges that bilingual language learners face with respect to written language? Here is an example of an easy way to block out mistakes: by Michèle Minor-Corriveau, PhD, 2015.  Dr. Minor-Corriveau received her Master's Degree in Speech-Language Pathology in 1998 from Laurentian University. She is a registered member of the College of Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologists of Ontario (CASLPO). Since 1998, she has worked with school-aged children presenting with speech and language difficulties and disorders. In 2012 she received her PhD in the area of Human Studies, an interdisciplinary doctoral programme focusing on integrating professionals from various backgrounds around a common complex problem. Her research interests center around, but are not limited to, creating standardized procedures for assessment and intervention of speech and language disorders targeting linguistic minorities, namely, the franco-ontarian population. Since 2008, Michèle has been providing lectures and teaches courses as an Associate Professor at Laurentian University in Speech and language pathology program. She is a strong advocate for francophones and francophiles alike, and is always honoured to help promote the profession of Speech-Language Pathology and its relevance in the bilingual setting. I like to participate in international conferences because it gives me the opportunity to see what other researchers who have an interest in child language are doing and how they are going about it. The Child Language Symposium in Coventry was just that. Coventry, which was once England’s capital, suffered severe bomb damage during World War II. We very much enjoyed walking through the historical sites of the city when we weren’t at the symposium so I’ve included some pictures in this post. Back at the University of Warwick, I found myself captivated by many different presentations. Many of which opened my eyes to the importance of cognition and resilience on language development. As much as I enjoyed presenting and talking about what goes on in my part of the world, I especially enjoyed the conversations I had with other professionals from Israel, England, Russia, Poland and elsewhere who are as passionate about this field as I am. In the paragraphs that follow, I will try to give an overview of what took place over three days with over 300 delegates!

We often don’t even think about how children learn language. It’s something that all kids do, and for the most part, they do it without any formal teaching. Our brains are extremely complex and it goes without saying that language is only possible because of the way we perceive the world, the way we think, the way we adapt and because of our innate desire to communicate with those around us. There were some very interesting talks on deaf children who grow up developing their own signs and gestures to communicate with their hearing parents and how they can convey meaning without words because of their strong desire to communicate. Fascinating stuff! Some researchers are looking at how using gestures can help activate the parts of the brain that are responsible for language, while others are looking at how theory of mind is a crucial ingredient in the recipe for language learning and language production. In a nutshell, theory of mind (ToM) is one’s ability to think about what other people might be thinking and how this can influence their actions. ToM is therefore very important for language development and communication. What I found most striking was how children are so resilient when it comes to language development. Even those who have many odds against them can develop adequate language abilities when given a chance. This is important to remember. It always makes me sad when I work with children who have difficulties with language, be it oral or written. How can it be that for some, language comes so naturally while others struggle so much? We can make a big difference. We can provide these children with the tools that they need to succeed. Because children can and want to succeed. There were many different speakers at this conference and all of them were trying to figure out how we learn language, how we use it and most importantly, how we can help those who struggle with it. Most of them showed that education is key. That is, educating parents, caregivers and teachers about the importance of language stimulation, book reading and peer interaction. It was reiterated several times during the conference that bilingual children, no matter what languages they speak, will have fewer vocabulary words in each of their languages than monolingual kids. This is not news, but it was a nice reminder to not be alarmed when bilingual kids don’t have the same vocabulary knowledge in each of their languages then native speakers. However, when you add up all the different words they know, they usually come out ahead of the game. Some studies that have been conducted in Europe included children who speak two, three and even four languages. Some have even shown a possible bilingual advantage such that learning more than one language helps them overcome some of the cognitive shortfalls that are associated with language impairments. As speech and language pathologists, most of us were trained to look at kids’ language skills only. However, many studies have shown that children need to have good memory, good attention, and good processing skills (executive functions, as they are called), among others, to learn language. We need to change how we think and look at language as a process of interactions between cognition and language. In fact, it doesn’t quite make sense to separate the two since they are intertwined in our brains. By looking at both of these elements we can better understand children, how they learn and how to help develop their language skills. I was pleased to see that there were a few poster presentations on ADHD and language. Although these were far and few between, they all showed that most kids with ADHD have pretty significant language difficulties, especially when it comes to social language skills. We need to work with kids with ADHD, but these kids often fall between the cracks, especially if they don’t have obvious language weaknesses. Social skills are extremely important to function and to be accepted in this very busy world. We, as parents, educators and speech language pathologists can help children develop social thinking and coping strategies. More and more assessment tools include a social skills component. Lets not ignore it. Being socially inept can be debilitating in this sometimes “dog eat dog” world. It was also shown that, as I mentioned in a previous post, many children with ADHD also have language impairments which puts them that much more at risk for academic failure, depression and segregation. Some studies also showed how kids with language impairments often have fewer friends and end up getting jobs that pay less then typically developing kids. I think that we can help break the cycle… These are only a few of the topics that were covered but it gives an idea of what the trends are right now in the study of child language. At the request of some readers, I will be posting our presentation and some of the posters that my colleagues, graduate students and I presented on my website under the “useful resources” tab. I am thinking of inviting a guest author for my next post. I will provide more details as soon as I have confirmation! Chantal Mayer-Crittenden, 2015 Pictures of our multi sensory room at Laurentian UniversityIn my last post, I wrote about developmental language disorders (DLD) and ADHD. I also wrote about how DLD often coexists with other non-linguistic deficits such as cognitive impairments, social difficulties, literacy deficits and working memory problems, among others. In fact, DLD often co-occurs with other disorders and some researchers suggest using a broader term such as neurodevelopment disability to account for all of the difficulties that may coexist. In this post, I would like to address sensory modulation as one of the disorders that coincide with DLD.

What is sensory modulation? In a nutshell, our brain allows us to receive, organize and interpret sensory input; be it auditory (sound), visual (vision), vestibular (balance), tactile (touch) or proprioceptive (sensing our own body in space). Some children have difficulties processing sensory information from their own body and from their environment. Sensory modulation is the process by which the nervous system regulates neural messages (from our sense) about different sensory stimuli around us. Children with sensory modulation difficulties will either respond to stimuli that typically developing children can ignore (ex. background noise). This is called sensory over-responsivity. On the other hand, they can sometimes show a lack of response to certain stimuli. For example, they may appear to be ignoring sounds or even verbal instructions. Finally, some kids are sensory seeking and/or craving in that they love touching things or watching bright lights, for example. Our ability to modulate sensory information allows us to generate an appropriate response that matches the demands and expectations of the environment. For example, if we walk into a room with a fan blowing nearby or a radio playing in the background, our bodies will often get used to the sensation of air blowing on our skin or to the sound of the music, allowing us to carry-on with whatever task we were about to complete. This is not always the case for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Children with SLI often have difficulties processing auditory input, learning the rules of language and registering the different contexts for language. They often have poor social skills, a lack of attention, difficulty with fine and gross motor skills, poor short term memory, difficulties with planning, organizing and sequencing thoughts, as well as problems with beginning and completing tasks. Adding to that, difficulties modulating the amount of sensory input they receive makes it that much more difficult for them to learn language. In fact, researchers have found that speech and language are an end product of sensory integration. Learning language involves more than just learning words. Language is social. In order to understand the context of a message, we need to process the information around us, be it facial expressions, tone of voice, body posture, hand movements, environmental cues, others’ intentions, etc. Children who have difficulties with sensory modulation often have difficulties understanding language. Who would have thought that language was so complicated? Looking at a child’s sensory modulation abilities could be helpful in determining a differential diagnosis for children with suspected neurodevelopmental disabilities. As I mentioned, children with DLD, autism and ADHD all have difficulties with speech and language, but research has shown that all three have different sensory processing issues. Within the context of a research study, my grad student and I have recently created a multisensory room in which we provide speech and language intervention using a multisensory approach to children who are diagnosed with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. I have included some pictures in this post for you to take a peek. Using the Sensory Profile, a questionnaire completed by the parents, we are able to adjust the sensory input we provide according to the child’s likes and dislikes. This room offers various sensory experiences, within an atmosphere of trust and relaxation, all the while stimulating or calming the senses. Multisensory environments have been used in physiotherapy and occupational therapy; however, research showing the efficacy of this approach in the field of speech and language therapy is scarce. For that reason, we are very excited about this study, and I can’t wait to try it with kids who have DLD! I know for a fact that my daughter would LOVE it in there! Inside this room we are able to work on narrative skills using objects and kinesthetic sand and water. The squishy sand often helps those who are tactile seeking. We are also able to adjust the lights to represent the time of day when the story is taking place. In fact, we adjust the lights according to the child’s sensory needs. We also have been using large puppets to create scenarios of social situations to address social thinking. We also use the mirror wall to practice facial expressions! The room is also useful for teaching social rules. It is a very different approach and takes some getting used to, but children are responding well to the multisensory room and are very engaged. We’ve included an aquarium with a fish to help teach responsibilities and to talk about expected and unexpected behaviors (i.e. with animals). With the help of textiles around the room, we are able to target semantic skills by categorizing objects according to how they look, how they feel and where they belong. There’s actually a lot going on in the room, but the sensory input relaxes the children, be it through dim lights, soft music or lavender essence. The children are able to focus on the tasks at hand in a very informal environment, which is very different for kids (and for Speech and language pathologists) who have been in session after session of traditional speech and language therapy intervention in a formal, school-like setting. This is still very new but I just had to share it with you! Through my research and my own personal experience, I learn a little bit more about SLI each day. One thing is for sure, if tapping into the different senses has a potential to help these kids learn, then I think that we should revisit traditional speech and language intervention and learn more about children's sensory profiles and needs. This in turn, might just help us help kids with DLD and other communication disorders make sense of the complicated world around us. We are social beings after all and we communicate using ALL of our senses so why not use all of the senses to teach language? Food for thought! I will keep you posted on the results of this study so stay tuned! Until then, thanks for reading! Chantal Mayer-Crittenden, 2015 My next post will be on July 28th. I will write about my experience and findings from the Child Language Symposium, Coventry, UK.

In this post, I would like to briefly touch on bilingualism and language impairment. That is to say, can children with language impairments successfully learn more than one language? As a speech and language pathologist, parents often ask me this question about their children, especially when it comes to choosing the language of instruction. It’s not an easy answer to give. It really depends on many factors, lets start first with what some of the experts have found.

In my practice, I often fall back on the work of two researchers: Dr. Kathryn Kohnert, speech and language pathologist and professor at the University of Minnesota and Dr. Fred Genesee, psychologist and professor at McGill University. Dr. Kohnert talks about the essential elements that are inherently related to the acquisition of a language. Language skills are developed in terms of Means, Opportunities and Motives. She calls it “MOM”. The individual must have, first and foremost, the Means to learn a language. That is, unimpaired cognitive, sensory, social, emotional, and neurobiological systems. Any deficiencies within these systems may cause difficulties in the acquisition and use of language. Second, Opportunities that offer a rich linguistic environment as well as positive Opportunities allowing for the acquisition and use of a particular language for rewarding communicative interactions must be present. Finally, the Motivation that may come from various sources is of ultimate importance: be it internal or external resources, environmental needs, opportunities and preferences associated with various social contexts. All these factors play an essential role in the acquisition and maintenance of language among children. Be it a first language or a second language. Children with specific language impairments have no frank neurological impairments, which means that they too can learn two languages if they are provided with opportunities and if they are MOTIVATED to learn both languages. In most cases, the children that I work with have the Means. However, because we live in a predominantly English community, it’s often the Opportunities and the Motives that are not up to par when children are also learning a minority language. This is especially true when almost all of the adults who speak the minority language also speak the majority language… Children sometimes just don’t see the need to put so much effort into learning the minority language. It is therefore our job, as parents, clinicians and educators, to ensure that children understand WHY they are learning two languages and give them reasons to WANT to speak BOTH languages. Dr. Genesee talks more about what is required for learning a second language. It’s as simple as TLC. After all, everyone needs a bit of Tender, Loving Care! However, for him, TLC stands for Thoughtful, Long-term Commitment and Creating an additive learning environment. He actually gave a very interesting lecture called “Early childhood bilingualism: Perils and Possibilities” on the Minerva series where he describes these elements in detail. You can listen to his podcast here. I will summarize them briefly for you but I do recommend you listen to the podcast. Thoughtful essentially represents that our job as parents is to plan our child’s language learning experiences so that our children obtain adequate exposure to both (all) languages. We need to make decisions about who uses what language and when as well as provide continuous and regular exposure to both languages. Bilingualism is a Long-term commitment. Parents need to be prepared and stick with it as well as make long-term arrangements that will ensure continuous exposure to both languages. It is important for parents to not change strategies or schools without serious thought. Finally, Dr. Genesee talks about creating an additive learning environment. The learning environment is crucial. While children have the capacity for dual language competence in the long run, it is not automatic and depends on the quality of the input. Parents need to be confident and to highlight the positive aspects of being bilingual. Creating opportunities to expand language learning such as playgroups, family holidays, regular visits with family members who speak the heritage language, etc. is of the utmost importance. Even when family members live far away, a lot can be done via Skype or Face Time. Here is a link to one parent’s blog who gives insightful ideas on how to make the most of Skype. Last but not least, we need to advocate for our child’s bilingualism. If we don’t, no one else will! To the question: Is bilingualism and SLI a walk in the park?, I answer “No”. But - there’s always a ‘but’ - neither is monolingualism and SLI. Children with SLI have difficulty learning language. Period. Be it one language or two, they will struggle. Bilingualism is possible and it is worth it if the two languages are valued in the family. For bilingual children who have SLI, the answer is not as simple as dropping one language. Nor should it be. The heritage language is just that: part of a child’s heritage. We need to remember that bilingualism isn’t always a choice, it’s intrinsically linked to our culture and it’s a way of life. Did you know that there are more bilingual speakers in the world than there are monolingual speakers? Yet we always seem to think that bilingualism is an exceptional thing! It’s not rocket science, we just need lots of patience and TLC! Like Marianna Du Bosq often says on her Bilingual Avenue Podcast: Bilingualism is a marathon, not a sprint! Embrace your child’s bilingualism especially if the minority language is part of your heritage. There are a lot of resources out there, many of which I will share on this blog in future posts. Thanks for reading! My next post will be on May 4th: "What IS a Heritage Language and Why is it Sometimes Difficult to Learn?" |

|

||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed